Policy is less protective of undocumented immigrants, more friendly to federal demands, than some

President Donald Trump appears to be making good on his campaign promise to penalize so-called “sanctuary cities” — local municipalities that refuse to cooperate with federal authorities in deporting, detaining, or collecting information on residents who may be in the country illegally. According to an executive order signed by Mr. Trump on Wednesday, the nation’s policy is now to force such cities into compliance by withholding the federal funds on which they depend.

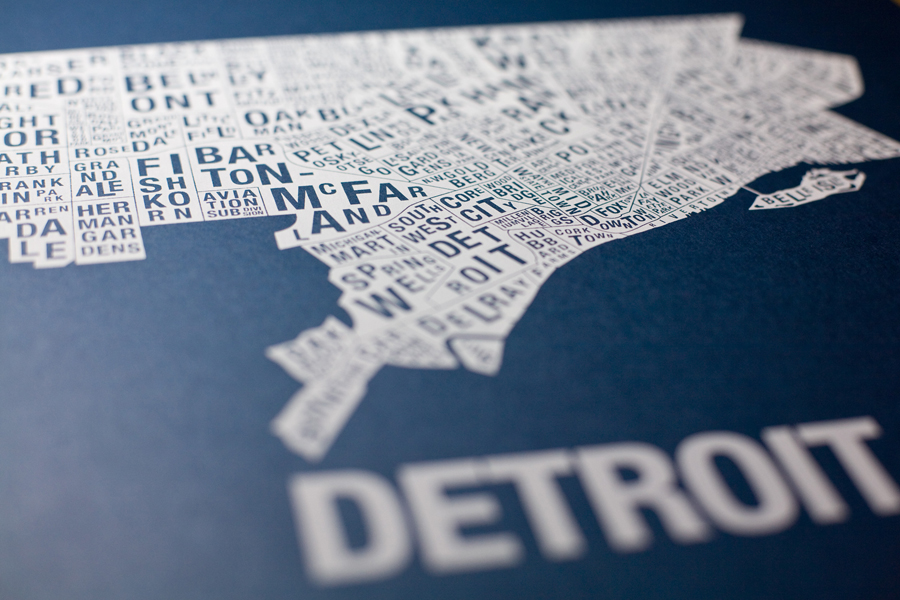

While some mayors are fighting back with a vehement defense of their cities’ policies — Bill de Blasio of New York promised to “defend all of our people … regardless of their immigration status” and Martin J. Walsh of Boston declared “if necessary, we will use city hall itself” to shelter those targeted by Mr. Trump’s order — Mayor Mike Duggan has seemed to downplay Detroit’s alleged sanctuary status.

“If Detroit police arrest somebody [who is] here illegally, they contact customs and immigration,” Mr. Duggan told Michigan Radio on Thursday.

But other Detroit officials, such as council member Raquel Castañeda-López, continue to say “sanctuary city” when describing Detroit’s policy towards the undocumented.

The conflicting declarations arise from the fact that “sanctuary city” has no precise legal definition, referring instead to a variety of policies that may describe a stronger stance in some jurisdictions but be less openly defiant in others. Detroit’s ordinance, adopted in 2007, is among the latter. While it does instruct city employees to provide equal services to all residents regardless of citizenship and generally instructs police not to ask about immigration status, there are exceptions — police may ask when conducting an arrest or when cooperation is requested by federal authorities. (Detroit does not use “sanctuary city” or any similar phrase in its legislation).

Chicago’s Welcoming City Ordinance and San Franciso’s City of Refuge policy, on the other hand, sit at the other end of the spectrum, specifically prohibiting police from detaining a person based on his or her immigration status, and mandating that city resources may not be used to assist federal authorities with deportations. Of particular concern to these and other cities is the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement “immigration detainer” policy, which asks cities and counties to, as described in Chicago’s ordinance, to “hold the [undocumented] individual for up to 48 hours after that individual would otherwise be released.”

These requests “are issued by immigration officers without judicial oversight, and the regulation … provides no minimum standard of proof for their issuance; there are serious questions as to their constitutionality,” according to the Chicago code.

Mr. Trump’s executive order, for what it’s worth, defines “sanctuary jurisdictions” as those who “willfully violate Federal law in an attempt to shield aliens from removal from the United States.” The extent to which cities are bound by federal law remains an open question, however, with legal experts challenging the proposed funding ban.

Miami has already given in to Mr. Trump’s demands, suggesting that other municipalities may soon follow.

Sanctuary city policies are intended to make communities safer by allowing undocumented people who witness crimes, or who are victims of crime, to communicate with police without fear of detention or deportation.

![Yeah, a Discovery! [Photo: Detroit Free Press]](http://www.locuspoke.us/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/imissthemegafauna1.jpg)