Detroit’s neighborhood names are on Google Maps now (actually, they have been since 2009 — does this mean we’ve finally achieved our dreams of becoming a world class city?) and other major Internet content providers have also joined the game, identifying and displaying the names of neighborhoods. Palmer Woods, Corktown, West Village — at last, we can geotag photos to them on Flickr, debate the merits of their dive bars on Yelp, and scope out their real estate on Trulia. Foundation-backed think tank Data-Driven Detroit has proposed using their boundaries to elect City Council members by district, and they’ve even spawned a series of cute, map-themed wall decor inspired by Chicago-based typographer Jenny Beorkum’s Ork Posters.

Let’s not get too excited, though! While some of these titles — Indian Village, Herman Gardens — describe historically and visually distinct sections of the city that are well-known among Detroiters, others seem to be, well… rather dubious.

Sherwood Park, for example, despite appearing on Google Maps (and a bunch of other places on the web) doesn’t really exist at all. The Eye is just about the coolest name for a neighborhood, ever, except for one problem: nobody actually knows that that’s what it’s called. And whoever thought Fishkorn was ever a good name for anything?

We might imagine that an authoritative, if long-forgotten, “official” map of Detroit’s neighborhoods exists somewhere. Perhaps the names and boundaries were agreed upon at some sort of naming convention that was held in the distant past. Or did Google just make them up? Do they ever change?

Neighborhood-naming strategies vary from one city to the next. Chicago’s 77 “Community Areas” were defined in the 1920s and the city publishes a map with precise boundaries. New York’s Department of City Planning, on the other hand, produces a map bearing a disclaimer in bright red: “Neighborhood names are not officially designated.” Some cities are only now beginning to name their ‘hoods: A volunteer-led initiative in Indianapolis — with some support from City Hall — last year delineated over 100 distinct sections of the city in an effort to foster some semblance of localized civic pride in the vast, 372-square-mile town.

Detroit, for its part, never standardized its neighborhood names. Most simply reflect common usage, even if some of them are more well-known than others. Some are inherited from defunct towns which ceased to exist when their land was annexed by the growing city of Detroit — Delray, Springwells Village, Five Points, Old Redford, Nortown. Others come from nearby landmarks, such as Osborn (a high school) and Palmer Park, while many, such as Lafayette Park, Grandmont-Rosedale and Boston-Edison, come from urban renewal plans, subdivision developers or the names of designated historic districts.

The names, and their boundaries, have remained dynamic: West Village was christened by an association of residents in 1974 to differentiate the mixed-use, mixed-density community from its easterly neighbor: the single-family mansions of Indian Village. East English Village was named in the 1990s after a poll solicited ideas from the community’s residents. And then, of course, there’s Midtown. Or is it Cass Corridor? As new names are created, old ones are discarded — like Old Germantown, which gave way to McDougall-Hunt, or the mostly-forgotten villages of St. Clair and Leesville.

So where did Google get its neighborhoods from?

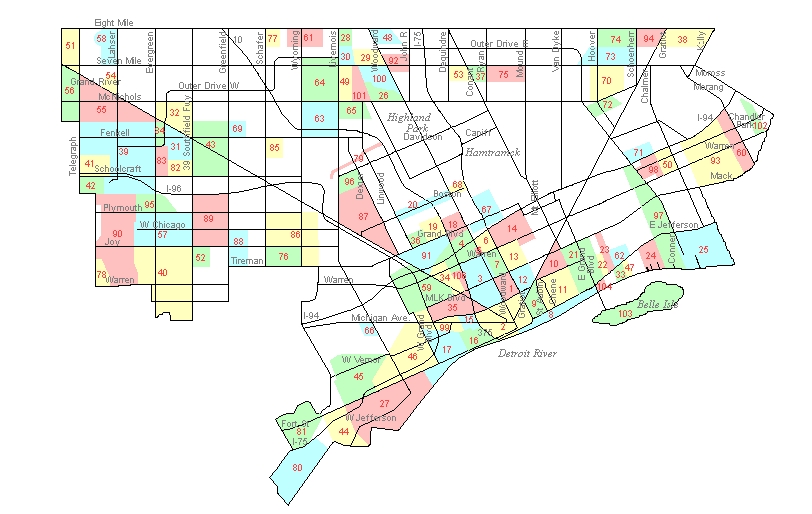

The best, and perhaps the only, shot at mapping them all out was made in 2003 by Cityscape Detroit, a grassroots advocacy group devoted to “good urban planning.” Cityscape president Arthur Mullen researched and identified a total of 97 Detroit neighborhoods and generated a map to display on the organization’s website.

Cityscape Detroit's 2003 map. Screenshot: http://www.cityscapedetroit.org/Detroit_neighborhoods.html

Mr. Mullen’s map, despite its precision, does not provide complete coverage of the city (note the white spaces in the above screenshot) and makes no claim to be the final, comprehensive authority on Detroit’s neighborhood boundaries. However, in a sort of butterfly effect that could have only originated in an earlier decade of the Internet, Mr. Mullen’s map caught on. When Google Maps began to display neighborhood details for the world’s major cities, they simply scraped the Cityscape map. In the months that followed, countless other Internet content providers, in turn, scraped Google’s data. Now, Mr. Mullen’s work has come to be used by pretty much everyone as the de facto Detroit neighborhood map.

How do we know this? Because Mr. Mullen (perhaps unintentionally) introduced a few spelling errors to his 2003 map. Like the fictitious trap streets that commercial cartographers place on road atlases to catch copyright violators, these misspellings allow us to track shameless duplications of Mr. Mullen’s data as they spread across the Internet. And these misspellings — “Van Steuban” instead of Von Steuben, “Fishkorn” instead of Fiskorn, for example — pop up everywhere. Even on Flickr, Yelp, and Trulia. The Mullen/Cityscape/Google/Everyone Else On The Internet neighborhood names have even, at times, served as sort of shibboleth that “real” Detroiters — whatever that means — have used to test the street cred of suburbanites, or to sniff out out-of-town journalists faster than they can say “212.”

In a piece written earlier this year, Dena Levitz in The Atlantic highlights the real power a neighborhood name can wield in an increasingly brand-conscious society. In cities around the country, Ms. Levitz writes, real-estate agents and community development organizations are working to rename (and rebrand) sections of town to suit their own objectives — sometimes over the objections of the people who live there. A 2009 map propagated by the San Francisco Association of Realtors wholeheartedly fabricates some neighborhood names: NoPa for what was formerly Western Addition, Yerba Buena for what was once part of SOMA. According to Meredith May of the San Francisco Chronicle, the map “is serious business — homes for sale through the Multiple Listing Service are automatically assigned to districts on the map, a factor buyers and real estate appraisers use to help size up a home.” Realtors in New York City frequently coin new names for increasingly tiny parts of town or spread older, more fashionable titles thin (in a geographic sense) to convey an air of trendiness upon a property to entice buyers.

Ms. Levitz cites University of Chicago sociologist Gordon Douglas: “The consequences of realtors providing misleading information are broad… working families are pushed out of rebranded neighborhoods as housing prices soar. Newer residents pay more to rent or buy.” New York State Assemblyman Hakeem Jeffries last year attempted to pass legislation that would prohibit realtors in that city from inventing contrived neighborhood names. It’s not quite clear how that’s supposed to work, what with the First Amendment and all, but for anyone who takes pride in his or her community and its name it’s hard not to at least identify, on some level, with Mr. Jeffries’s concern.

According to Mr. Douglas, “just on Yelp and Chowhound there will be huge debates about so-and-so pizza place and which neighborhood it’s in. With technology, everyone has basic GIS knowledge and will use Google maps and other location-based programs, so it’s always on our minds.”

Looks like the satisfaction that comes from feuding, block by block, over neighborhood names and boundaries isn’t just for Brooklynites anymore.

This story also appears in HuffPost Detroit.

Well, I’m the guy who worked on the original project to map Detroit into neighborhoods, and it was the best that we could do at the time on a volunteer basis.

Through out much of Detroit’s history, neighborhood names haven’t been very prevalent. A few areas have names while large swaths did not. The city grew extremely fast in the early 20th century, and there was tremendously rapid turn-over in many neighborhoods within 30-50 years of their construction. Maybe there wasn’t enough time for neighborhood identity to form here.

My goal was to begin the process of identifying neighborhood names for much of Detroit. I believe that neighborhood identity is important to developing community pride. Lots of Detroiter’s identify themselves as Eastsiders or Westsiders. Further identification of where one lived came from identifying the major cross streets near your house, not the neighborhood in which you live.

I wanted to develop a map that detailed the communities of our city, and one day hopefully lead to pride and identity in a specific neighborhood, instead of near an intersection.

A book identifying the neighborhoods and historic villages of Detroit helped to provide the project’s foundation. The book was written as a part of the lead-up to Detroit’s centennial. I used other maps and local knowledge to fill in a much of the City as possible. Many of the blank areas are industrial districts or the land-locked cities of Highland Park and Hamtramck, but there are still many areas without names.

GIS guru Alex Bellak transferred my neighborhood boundary information to the original GIS mapping files identifying specific boundaries. Another Cityscape Detroit board member, Andrew Koper transferred these files to a web application. It is during these transfers that some of the spelling errors may have been made.

We shared the information with the City Planning and Development Department and City Planning Commission, but they showed little interest. Case in point, the recent district maps created by the CPC for the creation of City Council boundaries ignored neighborhood boundaries.

The neighborhood mapping project was a great deal of work. I am excited that it has become the basis of lots of other data on Detroit.

Strong neighborhoods are often the building blocks of great cities. I continue to have this hope for Detroit.

Thanks so much for your comment. I have always been a fan of your map. One thing I’ve wondered: did Google ever ask permission to use your work?

nope. they never asked but we wanted to get the info out there. alex was excited with this article so it was a success.